Selma

On March 7, 1965, “Bloody Sunday”, peaceful marchers calling for voting rights were brutally beaten by state and local police in Selma, Alabama as they attempted to march to the state capitol, Montgomery. (See “Selma to Montgomery marches” in Wikipedia for more.)

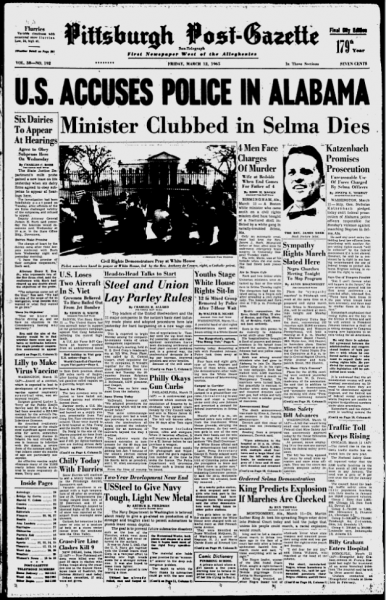

Photos and recordings of the violence were distributed to the national media:

Soon after the attack, journalists who were on the scene disseminated pictures and accounts of the brutality to a stunned nation. ABC TV even interrupted its evening movie with a special news bulletin that included fifteen minutes of video footage from the assault in Selma. The following day, the front pages of newspapers were filled with images and stories of the violence against those petitioning for equal voting rights. The confrontation, made especially salient by its vivid visual depiction, became a symbol of Southern efforts to maintain white supremacy at all costs. Writers called the day “Bloody Sunday,” and the bloodshed made many Americans feel shame and disgrace. Overwhelming numbers of citizens expressed shock that such an outrage could happen in the United States: The violence stirred the nation’s conscience and made a deeper impression than perhaps any demonstration during the civil rights movement.

— From “LBJ, ‘We Shall Overcome’“, an essay by historian Garth E. Pauley at Calvin College.

In the furor that followed, civil rights advocates called for President Johnson to take action to protect the marchers from the police.

The Sit-In

On Thursday, March 11, Sheila participated in the first ever sit-in at the White House, going on the official tour with eleven other youngsters, then sitting down when they reached the East Hall and signing “We Shall Not Be Moved”.

The administration excluded any media from the area of the sit-in, so the only photos we’ve found of the protest inside the White House come from the archives of Johnson’s Presidential Library:

The protestors said they would not leave until they had a chance to speak with the President about Selma.

The administration was initially uncertain how to respond, but after seven hours, the remaining protestors were arrested and dragged out by police.

The White House log shows that the sit-in was a frequent topic of conversation for the President that day, and that the order to remove the protestors was given by Johnson himself at 5:00. (See White House Logs From Sit-In.)

Timeline and Locations

The plan for the sit in was formulated in the afternoon or evening of the previous day, March 10.

On the morning of March 11, the protestors met that morning at the Fellowship Hall of St. John’s church, located a block away from the White House.

They then walked to the tourist entrance and entered separately. They had not previously gone on the tour or selected a spot to sit. They went most of the way through the tour and then spontaneously chose a location to sit down.

They first sat down in the East end of the Center Hall on the Ground Floor, outside the Library and Vermeil Room, at around 11:15 AM. (This spot is sometimes labeled the East Hall, but usually the entire area is referred to as the Center Hall.)

At around 1:15, they moved to the next room over, the East Garden Room, and stayed there until they were arrested. (A succinct timeline of events is provided in the Appeals Court ruling issued a year later regarding their case.)

An overhead view illustrating these locations was included in the New York Time’s report on the protest, and you can see them in the map for the current White House tours, which follow a different path than they did at the time, but generally go through the same areas:

You can view this area of the White House in Google Maps, which also hosts a panoramic walk-through of the Center Hall and the East Garden Room, which have not changed much in the intervening 48 years.

Protestors

There were twelve protestors in the initial group that sat down in the White House around 11:15. Two of them left during the course of the afternoon, while the remaining ten were removed by the police around 6:15. The names of the seven arrested protestors charged as adults were released to the press, while three minors were not named in police reports.

For many of the protestors, we only know the details included in those initial reports, typically age, race, and school or hometown. Piecing those together, along with some additional research, reveals the following information about the protestors:

Arrested and charged as adults:

- David Hunt Whittlesey, 21, male, White, Washington DC. (David now lives in Vancouver, and has remained involved in progressive politics, speaking at recent events in support of the Cuban Five and Bradley Manning.)

- Robert Edward Wooten, male, Black, Washington. (This may or may not be the same Ed Wooten who died on February 7, 2010 in Georgia.)

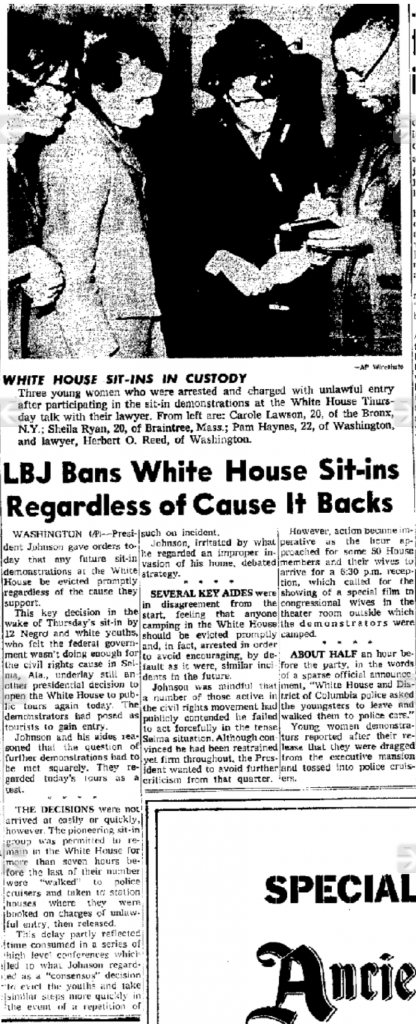

- Jessie Winifred McQueen, 21 (or 22), female, Black, Howard University, Washington DC, a native of Neptune NJ, charged at police station nearest to White House. (Here’s a picture of Jessie and Marta at the police station that night.)

- Marta Carole Kusic (sometimes reported as “Maria” or “Martha”, or “Kasic”), 18, female, White, Howard University, born in Brooklyn, NY, charged at police station nearest to White House. (Marta worked at “the RAT”, an underground newspaper, in 1968.)

- Pamela C. Haynes (or “Pam”), 22, female, Black, Washington DC. (Here’s a picture of Pamela, Sheila, and Carol speaking with a lawyer later that night.)

- Sheila Patricia Ryan, 20, female, White, Catholic University, from Braintree, MA, born in Oxnard CA. (Sheila’s life is covered in detail elsewhere on this site.)

- Carol Lawson, 20, female, Black, from the Bronx, NY. (Carol had worked on a literacy project in Selma in 1964, and was one of four SNCC members beaten at a Selma drive-in on July 4, 1964. She later married and changed her name to Carol Lawson-Green. Her life served as inspiration for “Night Catches Us“, a movie about former members of the the Black Power movement.

Arrested as minors:

- Lynn Wells, 16, female, from Garrett Park, MD, a high school student; not identified by the police because she’s a minor but mentioned in one article as a spokesperson and leader of the protest. (She was charged with a federal felony and received juvenile probation. She was a member of SNCC, and later other civil rights groups. She later married and changed her name to Lynn Wells Rumley. She runs the Textile Heritage Center at Cooleemee and serves as the town mayor.)

- Two other teenage girls whose names we have not been able to learn, one white and one black, both under 18, one of whom may have not been charged.

Left mid-day:

- Barry Wells, 14, male, White. Younger brother of Lynn Wells. Seen in this photograph outside the White House shortly before the others remaining inside were arrested.

- Eugene Harrison (known as “Rick”), male, Black, Washington DC. Identified at the time as affiliated with Howard University, but the Wells report he was still in High School. Spoke briefly outside the protest, said he’d been part of the original group.

In the crowd outside:

- Richard T. Brown, Washington DC, member Local 1 of the American Federation of Country and Municipal Employees, spoke outside the protest, In one press report Brown said he had intended to join the White House sit-in “but I got here late.” (Waterloo Daily Courier Thursday, March 11, 1965, Page 1.)

- A teenager who identified himself as “Chico” was photographed outside the White House and claimed to have been part of the protest group but does not appear in the photograph from inside the White House and was not recognized by the either of the Wells.

News Coverage

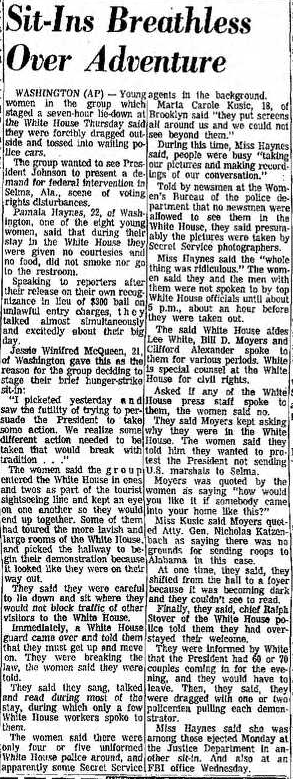

The sit-down was nationwide front-page news the next day, including the following:

Political Aftermath

The sit-in on Thursday, March 11 was part of an overall wave of pressure that led LBJ’s to order a Federal response on Saturday, March 13:

Your Government, at my direction, asked the Federal court in Alabama to order the law officials of Alabama not to interfere with American citizens who are peacefully demonstrating for their constitutional rights.

— From March 13 speech by President Johnson, archived at the LBJ Presidential Library.

In his speech to Congress on Monday, March 15, he proposed the legislation that became the Voting Rights Act of 1965:

The president was aware of the presence of the Lafayette Park protestors and especially those who staged a sit-in on the floor of the White House. As he introduced his proposed voting rights act to Congress on March 15, 1965, he praised the protestors from across the nation, thousands of whom were not far from his doorstep at the time.

— From “Citizen’s Soapbox, A History of Protest in Presidents Park“, at WhiteHouseHistory.org, operated by The White House Historical Association.

Two weeks later, with the protection of a federal court order and the federalized Alabama National Guard, the voting-rights protestors were able to proceed with their march from Selma to Montgomery.

Blocking Future Protests

However, while facilitating the protests in Selma, Johnson wanted to rule out changes of further sit-ins at the White House.

The AP reported that he’d ordered that any future protestors should be removed promptly by the police. (See Press Telegram: “Dragged from the Executive Mansion”)

In the same speech he gave calling for voting rights, he also signaled that protest would need to be governed by limits:

We must preserve the right of free speech and the right of free assembly. But the right of free speech does not carry with it–as has been said–the right to holler fire in a crowded theatre. We must preserve the right to free assembly. But free assembly does not carry with it the right to block public thoroughfares to traffic. We do have a right to protest. And a right to march under conditions that do not infringe the Constitutional rights of our neighbors. And I intend to protect all those rights as long as I am permitted to serve in this office.

— From the “We Shall Overcome” speech by President Johnson before Congress, March 15, 1965.

Legal Outcome

All seven protestors who were over 18 when arrested were convicted and sentenced to six months in jail. (At least two of the three arrested minors were also charged; one reports that she received juvenile probation for her Federal felony charge.)

Over the course of the next year, the case of the seven protestors was appealed, but the appeal was denied.

Sheila entered the Women’s House of Detention in the summer of 1967 and remained there until early 1968, where she was an uncooperative prisoner.